MIDLAND RAILWAY WORKSHOPS

FORM has hosted a wide range of practitioners at Midland since 2008, ranging from one-off site visits by leading designers, to intensive residencies by international creatives lasting several weeks.

In 2012 FORM invited Western Australian artist Eva Fernandez to produce a body of work inspired by the Midland Railway Workshops. Fernandez had recently completed two major exhibitions at some of the state’s most atmospheric heritage sites, the Fremantle Arts Centre and Heathcote Museum and Art Gallery.

Both these projects drew upon the sites’ histories as mental health facilities and utilised found objects from the buildings to represent the lives of their previous owners. Fernandez received funding from the Western Australian Department for Culture and the Arts to develop the new works at the Midland Railway Workshops, spending time on site in late 2012 and beginning her residency in earnest in early 2013. The outcomes of Fernandez’s residency premiered as part of the Midland Atelier 2008-2013 exhibition programme. She spoke with FORM Curator Andrew Nicholls mid-way through her residency:

Andrew Nicholls: What were your first impressions of the Midland workshop site?

Eva Fernandez: Walking into the site is like stepping into a past century. The sheer enormity of the space is overpowering. Entering the twentieth century industrial red brick buildings is almost a religious experience, similar to walking into a cathedral with its high ceilings and enormous cavernous spaces. Now dormant, the walls of weathered, painted red brick and repetitive huge steel structures have an undeniable presence that quietly overwhelms the viewer. Just as revealing is their present state of barrenness where hundreds once worked in structures that encompass several neighbourhood blocks. As Perth is a city whose physical fabric appears to be in a state of continual and often radical transition, there are not many structures remaining from this era or of this magnitude.

AN: You seem to be drawn to these types of abandoned sites as a source of inspiration. What is it about forgotten and antiquated buildings (and objects) that appeals to you?

EF: I am drawn to these spaces and objects because of their transitory state between stillness and imminent change. I am interested in the shifting landscape and the layering of history on these spaces as well as the loss and destruction of these histories. These abandoned sites show the evidence of human existence and interaction, though there is an overwhelming feeling of absence in these now dormant and neglected, decaying spaces. My images attempt to pay homage to the disappearing industrial architecture of previous generations as well as once-loved objects that show human interaction and use.

AN: Formerly speaking, much of the imagery comprising your recent, larger bodies of work would seem to fall within the genre of ‘still life’, yet to me they feel more like portraiture - you seem to treat items of furniture, luggage, saddles and even entire buildings, more like subjects (or bodies) ...do you classify your works as fitting within a particular genre?

EF: I find it difficult to categorise my work within a particular genre. I do however feel as though I treat my items of furniture, suitcases, buildings and objects, more like subjects than inanimate objects. This comes from the obvious evidence of interaction of the objects or structures with human beings and the character they take on with their dusty, cracked, worn or tarnished surfaces. Many of the objects I photograph are retrieved from abandoned houses and deceased estates which are rescued from being destroyed or discarded. The beloved material possessions we keep from a deceased relative, friend, or lover evoke memories and narratives. The presentation of these objects becomes as obvious as the absence of their owners. My artworks attempt to elevate the importance and meaning of these discarded and forgotten items and give them a new memorial function. Like early post-mortem photography, which was a common aspect of Victorian culture, these images represent a part of the mourning and memorialization process and remind us of our own impermanence and mortality.

AN: You specifically asked FORM to let you create work in the Elements Store, which is one of the most decrepit Workshops buildings, and one that has remained largely empty and abandoned since 1994 – what was it that attracted you to that space in particular?

EF: I was immediately attracted to The Elements Store because of its interesting structure. It is a unique building that stands alone and appears quite different to the others as it is constructed of wood and is quite small in comparison to the other brick structures on site. The textures of peeling paint and disintegrating wood panels reveal its age and give it immense character. The fact that it is also quite abandoned and somewhat neglected gives it a stillness and haunting atmosphere.

AN: You have also been working in Block 2 which is one of the most spectacular buildings on the site – what has it been like working in there?

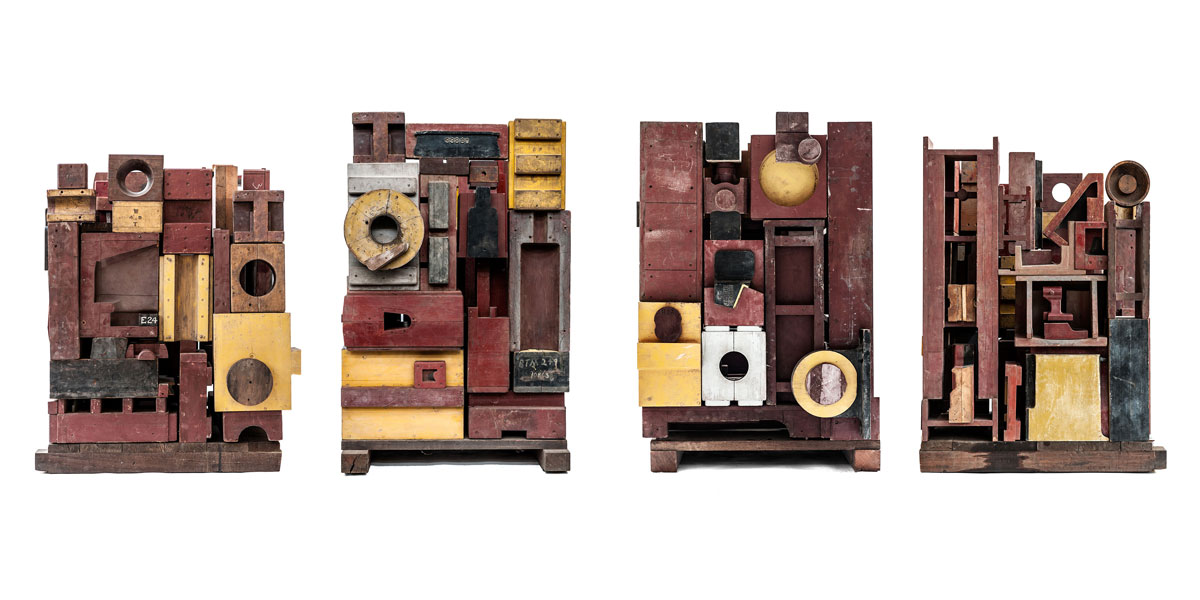

EF: Block 2 contains a plethora of visual feasts. At first it overwhelms with its sheer width, breadth and height. Then you start to notice all the amazing contents that are housed there. It was difficult to commence work because it was so overwhelming that your eyes don’t know where to rest. I was very attracted to the stacks old patterns that have been stored in an irregular manner on palettes. Each pattern, having been meticulously handmade by the industrial craftspeople of a bygone era, appears an artwork in itself. As they are stacked together with their muted tones of reds, yellows and blues, they make striking compositions which resemble the work of Modernist artists. These haphazardly placed assemblages inspired the photographic works which I am creating in the space.

ANONYMOUS SCULPTURES

These large-scale photographs of stacked wooden foundry patterns signify a transitory state of imminent change for these relics of a bygone era. As the receding industrial age has been revolutionised by advanced automated modes of manufacturing, these once modern objects have become obsolete remnants of a rapid, ever-changing and progressive world.

Each of the beautifully handmade objects, created with the craft of woodturning and carving, the métier of a bygone era, were then cast in metal to create locomotive parts and the entire rail system in the largest industrial workshop in Western Australia. Now they sit static in silence, abandoned with their dust encrusted surfaces and muted tones, housed in their huge, cavernous mausoleum of early 20th century red brick. Precariously piled on palettes they wait to be re-purposed or discarded.

The rigorous frontality of the facades of these structures and their isolation on a clinical, stark background, accentuate these utilitarian objects for their aesthetic value and allows the viewer to focus attention to their texture, tonality and surface details. These sharply defined objects, removed from their actual context, reveal the ‘essence' of the object’ through the formalised uniformity of the photographs.

The beauty of these objects is undeniable and accentuated when grouped together. The viewer’s eye hones in on each separate object - a reminder that each was designed and crafted by the human hand, a vanishing craft in the contemporary industrial landscape. These constructed assemblages are re-framed and re-presented as sculptural forms.

Eva Fernandez, 2013

THE ELEMENTS STORE

The Elements Store is one of the most decrepit buildings left on site, however as one of the Workshops’ earliest timber-frame buildings (erected circa 1910), it has significant heritage value. The building served a number of uses throughout the Workshops’ history, including housing the copper shop for a period of time. A century of industrial labour has left its legacy here, with the building today sitting isolated on field of clean-fill yellow sand, following substantial ground works to remedy contamination.

FLOWERS (FLORA OBSCURA)

Eva Fernandez undertook a residency at Midland Atelier over several months in 2012 and 2013. Using the Elements Store as one of the exhibition spaces, she has researched the native flora that would have once flourished on the Workshops’ riverside site. Her exquisite photographs follow from her previous memento mori series of objects from deceased estates, referencing forensic photography and the Victorian tradition of photographing the dead. Projected large-scale on screen in the space, they transform the decrepit building into a kind of mausoleum.

These photographic botanical studies of Australian native flora serve as mementos of the loss of nature in an environment damaged by industry. Exhibited on this specific site, celebrated for its contributions to the rail system and praised as the largest industrial workshop in Western Australia, demonstrates that progress does not come without consequence.

Clearing of land as well as contamination of soil, ground water and air are all consequences of this industrial activity. Where there is industrial activity there is environmental destruction and a continued dynamic shifting relationship between the forces of nature and culture.

Eva Fernandez, 2013